Written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

“He never did succeed in understanding, all his life long, how people could fail to be interested in other people.” - Oil!, Upton Sinclair

Histrionic, fatally confused and socially evasive, Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood is all the worse for its touching upon important subjects, oil and religion in American life. Putting the best interpretation on it, Anderson is simply way in over his head, with ultimately disastrous artistic consequences.

The filmmaker (born 1970) has chosen to tell the story of a fictional American oilman, set in California in the early part of the twentieth century. The film’s publicity variously suggests that There Will Be Blood is “based on” or “inspired by” Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel, Oil! Anderson himself says that Sinclair’s book “was a great stepping-stone.... [I]t’s only the first couple hundred pages that we ended up using.... We were really unfaithful to the book.” (www.avclub.com)

Anderson has the right to make any film he chooses, but it seems light-minded in the extreme to invoke Oil! as inspiration or even a “stepping-stone” while creating a work that only makes passing reference to a few sequences in the original novel, and radically transposes or alters those, sometimes to the precisely opposite effect.

There Will Be Blood is morbid and gloomy from its opening silent sequences, which, nonetheless, hold one’s interest. We first see Anderson’s Daniel Plainview (an impossibly portentous name, as opposed to Sinclair’s simpler “J. Arnold Ross”) mining for silver, on his own, in New Mexico in 1898. In the process, he comes across oil.

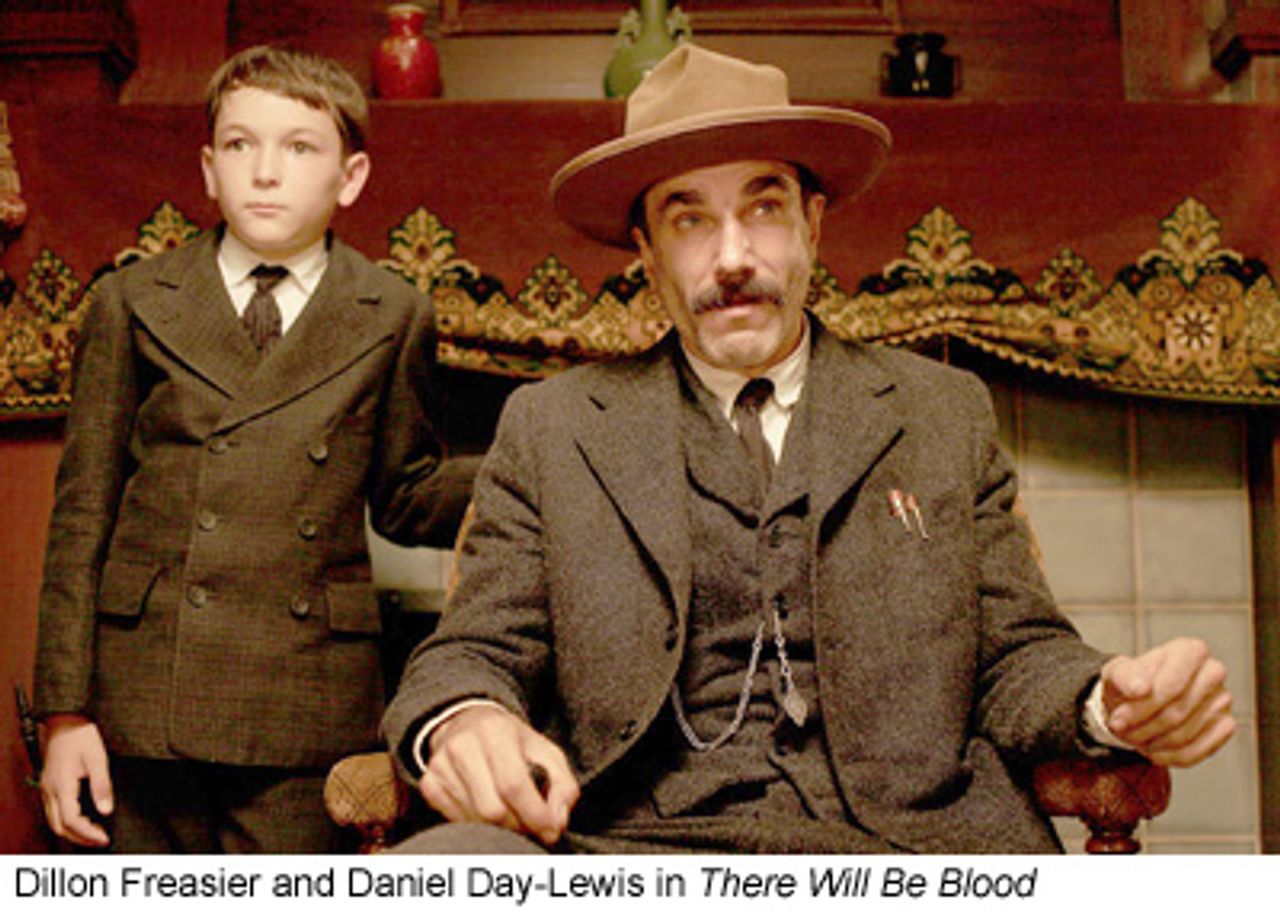

Plainview’s single-minded physical determination and individualism are emphasized from the outset. In one shot, clearly meant to be significant, we see the prospector (played by Daniel Day-Lewis) squatting, alone against the desert in the early evening, with something of a mad glint in his eyes. This fanaticism will only grow larger as the film progresses.

Several years later, having set himself up in the oil business, Plainview works away at one of his first operations. Threatening music (by Jonny Greenwood) plays over the images of the oil workers, filthy and menacing. By one means or another, Plainview ends up with an infant, whom he apparently adopts and brings along on business trips as an advertisement of his status as a “family man.”

By 1911, Plainview has become one of the most successful oilmen in California. A young man, Paul Sunday (Paul Dano), appears one evening and offers to sell him information about a property, his family’s farm, where oil is seeping out of the ground. The tip proves a good one, and Plainview eventually purchases the farm, not without some tough bargaining from Paul’s twin brother, Eli (also Dano), an aspiring evangelical preacher. Plainview buys all the available adjoining plots of land.

The new operation uncovers an “ocean of oil,” but Plainview’s son, H.W., loses his hearing when the liquid violently bursts forth from the ground.

This first portion of the film bears some vague relationship to Sinclair’s novel. Oil! is not a great work of art, but it is lively and observant. It was published, in 1927, during one of the richest periods of American fiction writing. Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer and Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith were published in 1925; and Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises the following year.

At times, Sinclair’s writing does rise to considerable artistic heights. The opening chapter of Oil! is a quite lyrical tribute to the automobile and the open road, from a young boy’s point of view.

It is worth noting some of the differences between the novel and the film—differences not bound up with the changes that inevitably arise from adapting a work to a different medium, but with distinct and even opposed artistic and social purposes.

Sinclair’s oilman, Ross, is an affable individual, a caring father, slightly overweight, largely uneducated although a shrewd businessman, thoroughly pragmatic. Sinclair introduces the one major speech that Anderson retains in the following manner: Ross “faced them now, a portly person in a comfortable serge suit, his features serious but kindly, and speaking to them in a benevolent, almost fatherly voice.” He “dressed like a metropolitan banker,” we are told, and had “the calm assurance of a major-general commanding, and the kindly dignity of an Episcopal bishop.”

Anderson’s Plainview is a different sort of animal: paranoid, unfriendly, secretive, a lone wolf—the director’s is a far more “radical” (and, frankly, trite) vision of a prospective oil baron. The film’s portrayal, however, throws the emphasis on Plainview’s personal monstrosity, while the novel matter-of-factly establishes that Ross lies, cheats and performs various corrupt and even brutal acts, not from personal wickedness, but as an inevitable result of the socioeconomic situation in which he finds himself.

Indeed, Ross remains likeable to the end of the novel, and continues to enjoy his son’s affection throughout, even as the latter becomes a “social reformer.” The older man’s defense of his misdeeds, when challenged by his son, is that there’s a “difference between a theoretical and practical view of a question.” As for bribing an influential politician or powerful man behind the scenes, it is simply “a natural consequence of the inefficiency of great masses of people” in a democracy; a corrupt official, on the other hand, “provided that promptness and efficiency that business men had to have, and couldn’t be got under our American system.”

Sinclair’s novel, in fictionalized form, takes in the Teapot Dome scandal of the 1920s (in which oil magnates bribed the Secretary of the Interior to allow them to lease public land for drilling). When Ross Jr. discovers that his father is planning to enter into a scheme to bribe government officials, he says, “It’s such a dirty game, Dad!” His father replies, “I know, but it’s the only game there is.”

Oil! is nothing if not expansive (perhaps too expansive) in its ambitions. The title of the book is somewhat misleading, as it seeks to make a more general survey of American political and social life in the first quarter of the last century. Sinclair’s Ross is loosely based on Edward Doheny (1856-1935), the oil tycoon, at one point reportedly the richest man in the US and one of those involved in the Teapot Dome affair.

The career of Eli Watkins is designed to bring to mind evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, whose Foursquare Gospel church gained an enormous following in the 1920s. Even the long-term relationship of William Randolph Hearst and actress Marion Davies is hinted at in the novel.

Sinclair, a socialist, attempts to bring to life the great political debates and controversies of the time. He treats the First World War, the Russian Revolution and the attempts by foreign governments to overthrow the workers’ state (at some length), as well as the ideological struggle between social reformists and revolutionaries. To Sinclair’s credit, although he was not a revolutionist, he provides the pro-Bolshevik elements with ample opportunity to make their case, and it is by no means entirely clear on which side the novel comes down.

Anderson’s Paul Sunday (again, an overly significant last name, presumably a reference to evangelist Billy Sunday, one of the models, along with McPherson, for Eli) makes only a brief appearance in There Will Be Blood, in order to sell out his family’s interests for $500. In Sinclair’s work, Paul Watkins, an extremely high-minded youth, innocently reveals the presence of oil on his father’s farm; he goes on to become a militant labor activist, a member of the early Communist Party and a political martyr, killed by a right-wing mob.

But then everyone (with the possible exception of Plainview’s son and the latter’s future bride, who have minor roles) takes a turn for the worse in the film as compared with the novel. The genial Ross, who merely believes that “practical” men like himself are obliged to bend the rules, becomes the misanthropic Plainview, who proclaims that “I see the worst in people,” whose life seems to be an accumulation of pointless hatreds and who murders two men in cold blood.

Details in the book are turned upside down for the sole purpose, apparently, of making the characters more malicious and their behavior more irrational. In the novel, for instance, moments before Ross’s operation begins drilling on the former Watkins’ farm land, the oilman goes out of his way to introduce Eli—whom he considers an outright fraud and a plague to “the poor and ignorant”—to the assembled crowd and encourages the preacher to give his blessing. Why wouldn’t the oilman desire friendly relations with an increasingly powerful evangelist?

In Anderson’s film, as the day when drilling will begin approaches, Eli asks Plainview if he may be permitted to bless the operation. At the eventual opening day ceremony, however, Plainview snubs the preacher—out of sheer perversity or ill will—in favor of Eli’s younger sister, Mary. Bitter feeling between the two men, not rooted in any obvious psychological or social facts, will only deepen over the years.

The labor process and the oil workers themselves undergo a transformation from novel to film. Sinclair’s attitude, as much as he criticizes the depredations of the private companies, is essentially sympathetic toward the discovery and production of oil. Ross’s son thinks to himself: “What could be more fun than a job like this? To know what was going on under the ground; to see the ingenuity by which men overcame Nature’s obstacles; to see a crew of workers, rushing here and there, busy as beavers or ants, yet at the same time serene and sure, knowing their job, and just how it was going!”

The men, too, as hard as they work, are not downtrodden and crushed. Sinclair describes the “young fellows in blue-jeans and khaki,” perched on top of trucks as the equipment is moved from one locale to another: “They sang songs, and exchanged jollifications with the cars they passed, and threw kisses to the girls in the ranch-houses and the filling-stations, the orange-juice parlors and the ‘good eats’ shacks. Two days the journey took them, and meantime they had not a care in the world; they belonged to Old Man Ross, and it was his job to worry. First of all things he saw that they got their pay-envelopes every other Saturday night...moreover, you got this pay, not only while you were drilling, but while you were sitting on top of a load of tools, flying through a paradise of orange-groves at thirty miles an hour, singing songs about the girl who was waiting for you in the town to which you were bound.”

In the film, the oil workers are nameless, faceless drones, ominous and interchangeable. This, again, is considered the “radical” view of things these days. In fact, it represents a diminution of life.

It is worth noting, for the historical record, that Anderson abandons the novel’s storyline entirely just prior to the first of two bitter oil-field strikes.

In any event, after that, the work is the filmmaker’s own creation, and it goes seriously off the rails, as Plainview rises to prominence in the oil industry, at the expense of his personal happiness, including his relationship with his son.

(It is best to draw a veil over the entire last sequence, set in 1927, which is disturbingly and thoroughly misconceived. Daniel Day-Lewis attempts to make up for the absurdity of the events, which come largely out of the blue, by sheer force of will, with ever diminishing results. The over-acting here is in inverse proportion to the emotional and social authenticity of the drama.)

Plainview’s growing lunacy simply goes unexplained. Very wealthy individuals may go entirely mad, like Howard Hughes, or not, like Warren Buffett. An artist makes it very easy for himself if he or she simply implies that the acquisition of wealth and power in and of itself is enough to drive someone insane. The lack of concrete connection between Plainview’s social existence and his mania tends to conceal, rather than lay bare, any mentally devastating social processes that might be at work.

Critics foolhardily compare There Will Be Blood to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. The bracketing of the two works could hardly be less apt. Kane is an extraordinarily talented man, with many attractive qualities, whose misfortune it is to be immensely wealthy. Given another set of social circumstances, he might have done truly great things. He is hemmed in and ultimately destroyed by monstrous social relationships. Can anyone seriously make the same claim about Anderson’s protagonist?

The social structure into which Plainview enters may be monstrous, but insofar as it is, it only suits and encourages his own essential deformities. The social relationships are rotten in There Will Be Blood because men and women are rotten, the film implies. This is simply wrongheaded and disoriented.

This is where social and political evasiveness, aided by historical ignorance and a blind faith in a “largely intuitive” creative process, enter the picture.

What could have been a scathing assault, through a reworking of Oil! or otherwise, on corporate America and fundamentalist religion is no such thing, despite the claims of various “left” critics and wishful thinkers. Of course Anderson is under no obligation to launch such an assault if he doesn’t believe one is necessary, but choosing Sinclair’s novel and then systematically declawing it seems an almost provocative act. It suggests that the filmmaker recognizes the significance of oil and religion in contemporary America—whose establishment, after all, has launched a brutal, neo-colonial war over Middle East energy resources—but then hasn’t the commitment or seriousness to see the process through.

His comments to various interviewers reveal some of this. Fashionably, Anderson chooses to distance himself from any concern with making a social critique. Asked how aware he was of “the film’s subtext about class, religion and money,” Anderson replied: “Well, aware of it to know that if we indulged too much in it, or let that stuff rise to the top, that it could get kind of murky. And it’s a slippery slope when you start thinking about something other than just a good battle between two guys that kind of see each other for what they are, just trying to work from that first and foremost and let everything that is there fall into place behind it. I would be wrong—it would be horrible to make a political film or anything like that. Tell a nasty story and let the rest take care of itself.” (www.thedeadbolt.com)

But bitter experience teaches that “the rest” never does take care of itself, not without the conscious, deliberate intervention of the artist. No one has any use for a “political film” that is didactic or pat, or knows all the answers, but Anderson is excluding the possibility of an artistic, spontaneous and insightful examination of social life as a whole, the possibility of presenting the big picture.

Asked by another interviewer whether he had been thinking about “modern-day strong-arm capitalism and mega-church religion” while writing and shooting his film, Anderson said, “I was thinking that we’d better be very careful not to do too much of that.” Why? In any event, Anderson succeeded. He didn’t think too much “of that” and hence the film, despite some interesting and intelligent moments in its first two thirds, is neither genuinely radical nor thought-provoking. It’s a great mess, in fact.

Consciously or not, the filmmaker avoided a head-on criticism of American capitalism and its ideological defenders among the fundamentalists that would have brought attacks on him from the media and perhaps damaged his career.

Filmmakers are going to have to reorient themselves and learn to think about a host of important, complicated matters. It’s a difficult process and it involves struggle and sacrifice, but the future of the art form depends on it.