With the kind permission of Adelbert Reif, we are publishing here a review of Red Star Over Russia, which was named photo book of the month in the German magazine Universitas. The review appeared in the August edition.

It is no exaggeration to say that David King’s Red Star Over Russia is a truly superlative photo book! Never has the three and a half decade-long history of the Soviet Union—from its beginnings until the death of Stalin—been given such a dramatically visual presentation as in this book.

Since the end of the Soviet Union some 20 years ago and the limited release of a series of early Soviet archives for Western researchers, several photo books about the development of the Soviet Union have appeared. Memorable in this respect was the volume Russia and the Soviet Union (2007), published by Peter Radetsky, who mainly used photographs from the TASS state news agency to present a century of Russian and Soviet history.

None of these often lavishly compiled publications achieve the broad thematic range and exceptional diversity of the historical material offered by David King. The reason for this is to be found in the author’s personal development. King—author of The Commissar Vanishes, The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia, The Victims of Stalin (2003), as well as numerous other books about the Soviet Union— headed the London Sunday Times cultural department from 1965-1975. His private collection of Russian revolutionary art consists of some 250,000 objects—mainly posters, newspapers, leaflets and photographs—and is considered one of the most extensive and important in the world.

More than 500 pictures are reproduced in outstanding quality in the current volume and accompanied by King’s concise—yet, in their explanatory power, extremely memorable—historical-political commentaries. Many of them are to be seen here for the first time, and—thanks to the expressiveness of his chronologically arranged pictures—no conventional history book could so directly and candidly highlight the shattering events of the years 1917 to 1953 as does King’s volume.

A further positive feature must be mentioned. By reproducing their works, King has rescued from oblivion numerous Soviet designers, artists and photographers of the Twentieth Century, who were murdered or died in the Gulags during Stalin’s reign.

Of course, King knows full well that his book will fail to deliver a learning experience that is “pleasurable”, in the conventional sense of the word. “The reader is warned,” he writes in his introduction, “the going won’t be easy. During the four decades covered in these pages, tens of millions of Russians suffered from the consequences of three wars, two famines and a totalitarian dictatorship. After Lenin’s death, Stalin acquired such a degree of power that he was able quite arbitrarily to turn the life of a normal citizen and especially a high-ranking communist into a nightmare of arrests, interrogations and torture—followed by brutal years in a Gulag or confrontation with a firing squad.” This is exactly the situation King wants his readers to imagine for themselves.

The volume begins conventionally enough for a photo book. In a picture from 1900, the tattered figures of so-called “barge haulers” or “Volga boatmen”, labouring along a bank of the Volga, drag ships on the river by long heavy ropes, while the photo directly following shows Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra Feodorovna with their two eldest daughters, Olga and Tatjana, on a pleasure boat trip in 1909. The social contrast assaulting the eyes reveals what in Russia—the most authoritarian country in Europe at the time—had to come: the Revolution, an enormous upheaval that would shake the world. Here, with the two revolutions of February and October 1917, King engages with full force the main theme of his “visual” presentation of the following decades of Soviet history.

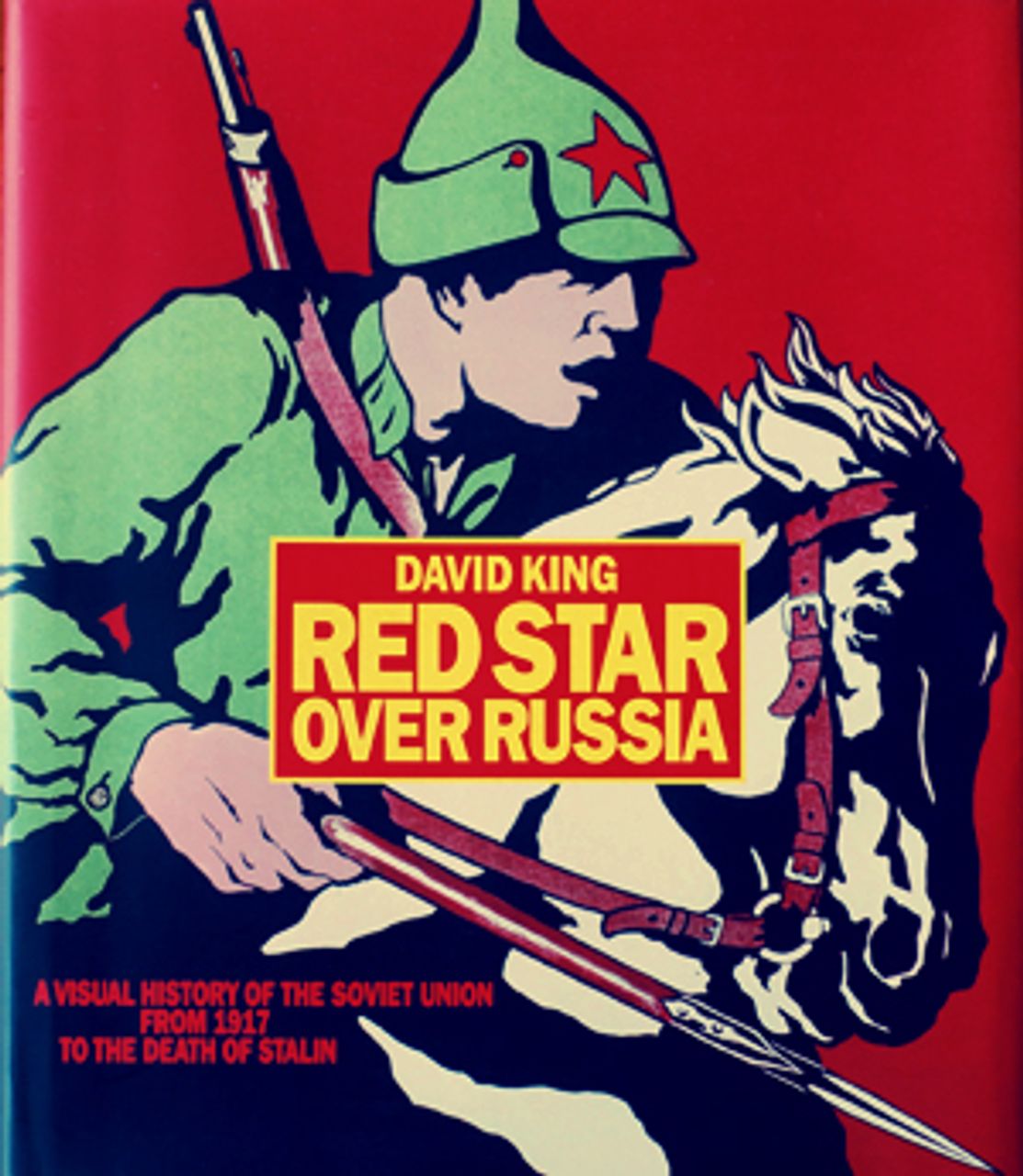

It is not only the immediacy of the photographic documentation of the days of the Revolution that makes such a tremendously strong impact. King also provides us with artistic testimony in the form of title pages from various newspapers, book jackets like that of John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World, drawings and posters that charted the revolutionary upheavals whose artistic forms bore a revolutionary, avant-garde character.

In addition to this, the production of photographic portraits of their leaders was an important issue for the victorious Bolsheviks. Thus in 1918, the well-known portrait photographer, Mosei Nappelbaum, created on their behalf one of the most famous portraits of Lenin, reproduced in millions of copies. (Another evocative photo portrait of Lenin, taken in the Kremlin in 1919, came from Viktor Bullas.) Apart from his photos of Lenin, Nappelbaum composed a photomontage in November 1918, entitled “Leaders of the Proletarian Revolution”: this shows Lenin, Zinoviev, Lunarcharsky, Trotsky, Kamenev and Sverdlov.

Then in 1919, he produced a particularly impressive photographic portrait of Trotsky, founder and leader of the Red Army during the civil war at the height of his powers. King also provides a number of extremely interesting historical photos of Trotsky at different stages of his political career, including a rare cubist-futurist portrait by an unknown artist from late 1920. From the end of the 1920s—Lenin had died in 1924, and Trotsky was, step-by-step, deprived of power by the clique around Stalin—the possession of anything to do with Trotsky or the so-called “enemies of the people” meant arrest, the Gulag or a sentence of death.

David King devotes a considerable part of his work to the cultural and educational enterprises of the Soviet state. Anatoli Lunacharsky played a leading role in this respect, and King provides a photograph of this imposing intellectual together with his wife, the silent film star Natalia Rosenel, taken in the mid-1920s. King explains, “Lunacharsky came from a well-educated, radically minded social environment, and his great rhetorical talents placed him at the centre of the Revolution”.

In November 1917, Lenin saw to it that he became the first commissar for education and enlightenment. Lunacharsky used his post to direct a rigorous campaign against Russia’s widespread illiteracy. He reformed the education system, brought teaching methods up-to-date and encouraged the masses to develop interests in music, theatre, literature and the visual arts. When he retired from office in 1929, everyone of the appropriate age could read, write and calculate.

Lunacharsky also promoted the idea of combining art and design in a variety of fields. Among the leading artists, designers, architects and film-makers of the avant-garde—who in the 1920s taught in the Higher Art and Technical Studios in Moscow, specially set up for this purpose and known by the acronym Vkhutemas—were El Lissitzky, Ljubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Vesnin. However, the work of these first-rank experimental artists and designers was soon to be regarded with increasing hostility by the representatives of so-called “social realism”, and the Vkhutemas closed in 1930. Like many Soviet artists and writers of the avant-garde, Lunacharsky often had to stand up to narrow-minded Bolsheviks when it came to cultural issues. He died from a severe cardiac defect in 1933, a fate that doubtless saved him from falling victim of the Stalinist terror campaign that began shortly thereafter.

David King dedicates the most moving pages of his book to the documentation of this terror. Early in the volume, one sees an unretouched photograph of Stalin, entitled “The Butcher”, followed by photos of the forced labour of Uzbeks (1930) and one showing a troop of work slaves in temperatures well under zero during construction of the Stalin Belomor Canal, that was planned to connect the Baltic Sea and the White Sea (early 1930s).

Tens of thousands of workers died while building this canal, which had been personally commissioned by Stalin but was hardly ever used after its completion. A page of police photographs—identifiable from the code numbers they bear—showing children “of traitors of the socialist motherland” in a children’s home, set up by the secret police in the 1930s, document a particularly tragic occurrence: these children were instructed by their teachers to denounce their parents, even if they were no longer alive. In order to signify the gross contradiction of this stage of early Soviet history, King continually inserts contemporary slogans into the artistically designed, full-colour propaganda posters—such as “The USSR is at the centre of international socialism”, “Communism means Soviet power plus electrification” or “Long live our happy socialist country! Long live our beloved leader, the great Stalin!”—thus frequently symbolising the parallel world of Soviet socialist surrealism.

In addition to photography depicting the misery of the catastrophic famine in the 1920s and the persecution of the kulaks, pictures evidencing the most devastating instances of the Stalinist tyranny include those—made by the secret police—of defendants in the Moscow show trials of 1936, 1937 and 1938. Most of these portraits are to be seen here for the first time. The faces clearly show signs of the torture the victims suffered before utterly absurd and irrational confessions could be wrung from them—faces like that of Gregori Zinoviev, principal defendant in the first show trial (well-known as the trial against the “Trotskyist-Zinoviev terrorist core”) in August 1936. These faces express sometimes horror, sometimes incredulity but also sometimes indifference in view of the events, staged on Stalin’s orders but incomprehensible to those affected.

Stalin considered conducting a fourth show trial, this time against Soviet writers and artists. Vsevolod Meyerhold was arrested in June 1936, after staunchly refusing to associate himself with “social realism”. The Meyerhold police photo presented by King also evidences the brutal torture, described so precisely by the great theatre director in a letter to Molotov that is also reproduced here. Meyerhold’s wife, the actress Sinaida Reich, was murdered a week after his arrest. Meyerhold himself was shot on February 2, 1940.

For decades, the photographs lay in a Siberian archive, now administered by the Russian Federation’s domestic secret service. King writes that, “The enormous significance attached to them can be gauged from the fact that—for the purpose of compiling this photographic volume—they were transported to and back from Moscow in a specially arranged train”.

With Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, another bloody stage of its history began for this vast country. The photographs chosen by King from the “Great War of the Fatherland”, together with a series of contemporary posters designed to stir the population to war, document a horror scenario that ended with the deaths of 18 million Russians—some estimations claiming up to 24 million. King writes, “The reconstruction of industry and agriculture placed huge demands on the country. Soviet infrastructure lay in ruins. The Nazis had completely destroyed more than 1,700 towns/cities and 70,000 villages, as well as 65,000 kilometres of railway track, hospitals, schools, libraries and museums. Everything had to be built anew”. Even after Stalin’s death in 1953, it was to take more than three decades before Russia began to slowly free itself from the tyranny it had been forced to endure.

Some readers will certainly regret the occasional important detail missing from King’s “visual” history of the Soviet Union. Oddly enough, for example, the author has almost completely ignored the cinematographic side of Soviet art. But this notwithstanding, Red Star Over Russia presents through both its images and its text an inimitable panorama of an important part of Russian-Soviet history in the Twentieth Century—the “century of the wolf” and the “century of tears”, as Nadezhda Mandelstam called it.

Copyright Adelbert Reif and the Universitas magazine, published by S. Hirzel of Stuttgart, (http://www.hirzel.de/universitas/)