The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City is one of the most powerful institutions in the international art establishment, mounting “blockbuster” exhibits each year that draw huge crowds. Of the 16 exhibits worldwide with the largest attendance last year, seven of them were at MoMA. Arts reviewer Clare Hurley visited the museum earlier this year when three such exhibits were concurrently on display—retrospectives of Marina Abramovic, William Kentridge and Tim Burton. The following review examines the work of two of these artists.

Marina Abramovic has, for good reason, called herself the grandmother of performance art. She has been using her own body as “the subject, object, and medium of her work” since the early 1970s.

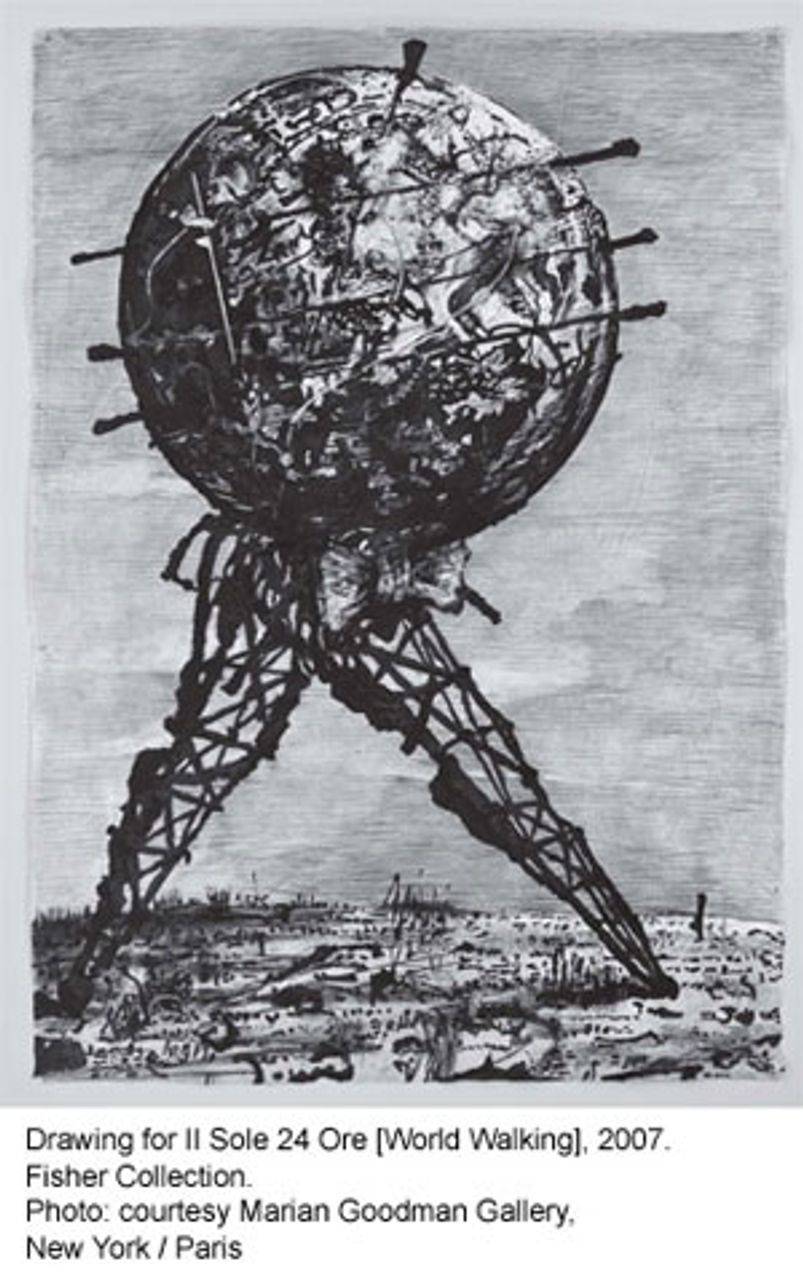

Much of William Kentridge’s work deals with apartheid in his native South Africa. This past year, at the same time as the exhibit at MoMA, he was also directing the Shostakovich opera The Nose, from the story of the same name by the early Russian realist Nikolai Gogol, at the Metropolitan Opera. (See “Shostakovich’s The Nose finds its way to the opera stage”)

And Tim Burton? Considered a talented film director and designer, especially by his fans, his extravagant and quirky films—Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, Sweeney Todd, and most recently Alice in Wonderland, to name just a few—inspire a cultish following. Why Burton deserves a retrospective in an art museum is not altogether clear, but the show appears to have been included to draw crowds, and it was successful in that respect.

What did these exhibits have in common, if indeed they had been intended as a group? Not surprisingly, the work of all three is multi-media, with a predominance of performance and video; exclusively, in the case of Abramovic, and combined with drawing, printmaking and film/set design, in the instances of Kentridge and Burton.

Accordingly, there were a lot of video monitors in all three exhibits, simultaneously projecting loop tapes of frenetic images and sounds. Invariably one arrived somewhere in the middle of one loop and left somewhere in the middle of the next. It took a sustained effort to figure out what the artist sought to communicate, whereas everything about the conditions of viewing the work kept you distracted and urged you along.

More importantly, as retrospectives, the exhibits were an opportunity to trace the problems of development of this particular generation. The artists are roughly contemporaries, although Abramovic, born in 1946, is a decade older. Their collective work spans the last four decades and, taken as a whole, parallels the artistic trajectory of the past three or four decades.

This process was most apparent in Abramovic’s work. The centerpiece, literally and figuratively at MoMA, was her piece The Artist is Present. Abramovic sat at a table in the center of MoMA’s atrium every day of the exhibit—more than 700 hours in total. Museum visitors were invited to sit across from her for as long as they liked, without speaking. Tick marks on the wall signified how many hours had been completed. The wall caption explained that that the familiar configuration of table and chairs has been “elevated to another domain, a place where nothing—or possibly everything—happens.”

The piece encapsulates what has become of performance art in its 40 years. Traces of its roots in various avant-garde art movements of the early 20th century that sought to “shock the bourgeoisie” have grown shopworn. In the context of MoMA’s elegant atrium, the piece seemed more stately than provocative.

The piece encapsulates what has become of performance art in its 40 years. Traces of its roots in various avant-garde art movements of the early 20th century that sought to “shock the bourgeoisie” have grown shopworn. In the context of MoMA’s elegant atrium, the piece seemed more stately than provocative.

The real value of the retrospective was that it gave one a sense of what such performances were like in an earlier period, through the original video recordings from the1970s of her work with partner Uwe Laysiepen (Ulay). These were projected on monitors, as well as simultaneously recreated by live actors/artists in the galleries.

Abramovic and Ulay met in Amsterdam in 1976 and formed an intense personal and professional collaboration. Much of the strength of their work resides in the physical magnetism of the pair—Abramovic at 64 remains strikingly beautiful—and their ability to withstand pain (and probably boredom) without flinching.

Pioneered by such artists as Yves Klein, Joseph Beuys and Vito Acconci, as well as Abramovic, who were born or came of age in a Europe still shattered by World War II, performance art arose in a period of mass movements—for civil rights and against the Vietnam War in the United States, the May-June 1968 strikes in Paris, the revolutions against the military juntas in Greece and Portugal, and the struggle against the Franco dictatorship in Spain in the early 1970s.

Like Dada and the bohemian artists of Montparnasse in earlier periods, these figures sought to express the anti-establishment mood of youth and intellectuals intent on challenging bourgeois norms of behavior, exposing what emerged when the usual constraints of civility were removed.

In Rhythm 0 (1974), a piece that remains disturbing in the video, Abramovic stood for six hours while spectators were invited to do anything they wanted to her body, using objects from lipstick to flowers to knives, whips and a gun (all the props were reproduced at MoMA but without a live re-enactment). They cut off Abramovic’s clothes, wrote on her body and sliced her with razors, while she remained impassive. One visitor held the loaded gun to her head until another wrestled it away.

But performance art evolved alongside the political and social history of the period. If the mass struggles of the working class had taken a different path, they would surely have affected the development of avant-garde artistic trends. The betrayals of the struggles of the 1970s led to a period of disillusionment that had its impact on the performance artists and the radical milieu of which they were a part. To the extent they still saw themselves as challenging the existing order, they did so increasingly through displays of passive resistance, provocative sexuality and other gender issues—the image of the male/female nude body was emblematic of Abramovic/Ulay’s work.

Ultimately the pair became interested in Tibetan Buddhism, traveled widely through Europe, Australia and Asia (their van was also on display at MoMA), and ended their partnership in 1988 by each walking half of the Great Wall of China—she from the Yellow Sea and he from the Gobi Desert—to meet in the middle and say goodbye.

Since its heyday, performance art has lost much of its impact, even as its legacy continues to shape the parameters of what is considered art. Abramovic has complained that her work, and performance art in general, is misunderstood, which is why she wants to recreate it for a new generation of audiences and train a new generation of performers.

But the problem is not simply a lack of understanding on the audience’s part, or of insufficiently provocative acts by the performers. In MoMA’s re-creations, there was little that seemed to move the relatively prosperous and complacent audience one way or another.

The only piece that got a bit of a rise was the re-enactment of Imponderabilia (1977), in which two nude models (originally Abramovic and Ulay) stood about a foot apart from one another, with spectators invited to squeeze between them. At MoMA, a visitor reportedly groped one of the performers, a not entirely unexpected response when thousands of individuals are invited in turn to press up against a naked stranger. This visitor was asked to leave and his museum membership was revoked.

The only piece that got a bit of a rise was the re-enactment of Imponderabilia (1977), in which two nude models (originally Abramovic and Ulay) stood about a foot apart from one another, with spectators invited to squeeze between them. At MoMA, a visitor reportedly groped one of the performers, a not entirely unexpected response when thousands of individuals are invited in turn to press up against a naked stranger. This visitor was asked to leave and his museum membership was revoked.

Since the 1990s, Abramovic’s work has examined her family origins in post-war Yugoslavia and her reaction to the conflicts—fueled by the resurgence of ethnic nationalism and its exploitation by rival cliques emerging from the Stalinist bureaucracy—which resulted in its violent breakup.

Her response has become an increasingly ascetic one as her outlook has become increasingly pessimistic. Her self-punishing rituals more and more explicitly resemble the flagellations of the early Christian saints. In one of the last videos in the exhibit, she spreads herself out naked on a crucifix made of ice, flinching only slightly at what must be incredible pain.

This increasing resort to spectacle—a kind of one-woman gladiator arena —is bound up with a turn away from earlier attempts to reveal something about the world, which, however imperfectly, Abramovic had sought to do in her earlier work.

A similar trajectory is found in the work of William Kentridge. Five Themes, the retrospective of the South African artist’s work, was on display at MoMA concurrently with that of Marina Abramovic.

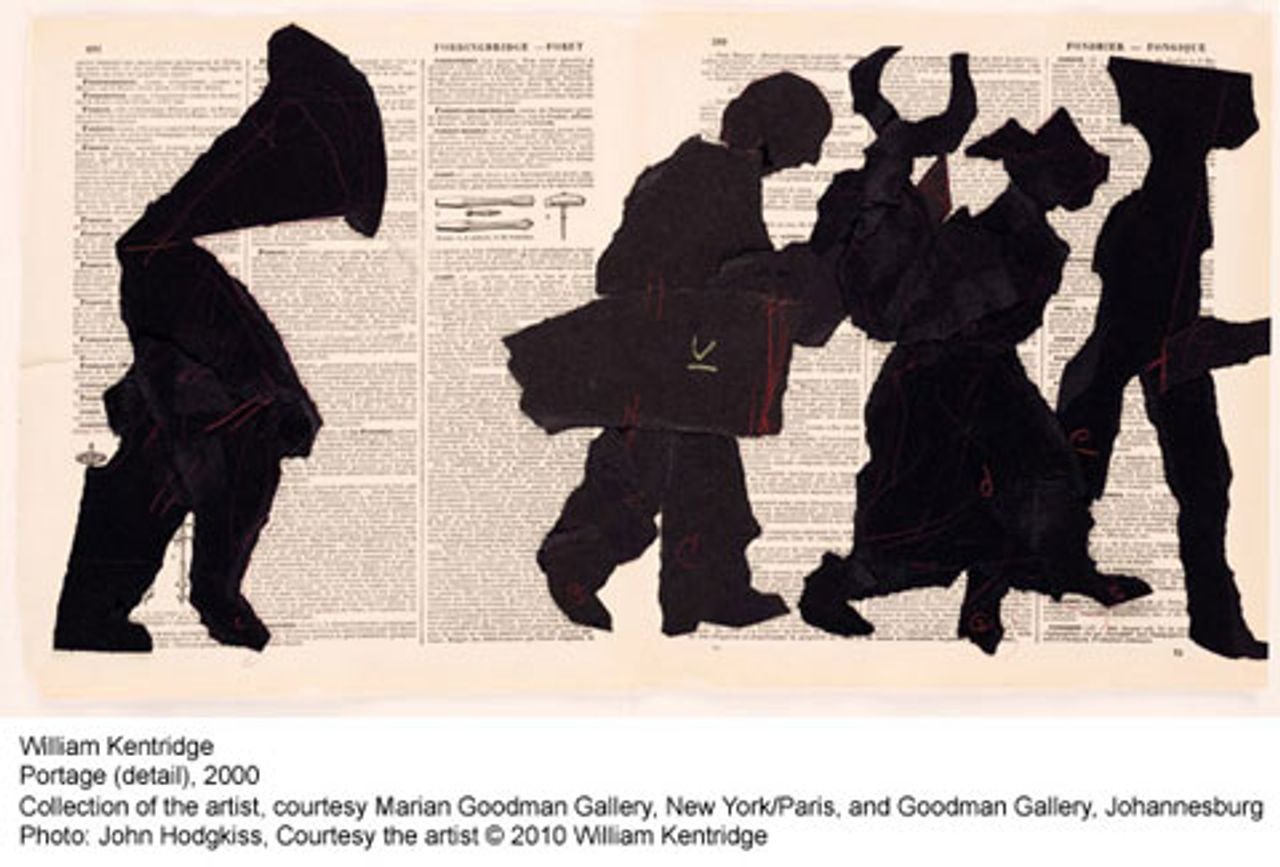

Kentridge first gained international attention in the early 1990s with his unique animated drawings—he has called them “stone-age animation”—depicting the uprisings against apartheid in South Africa. He drew and erased his charcoal drawings, recording the development with stop action film to create videos that are literally “moving pictures.” Some of the videos also include black-paper silhouettes, figures drawn in white chalk, as well as black and white news footage and documentary sound.

Kentridge’s videos preserve the feeling of wonder that can still be evoked by a hand-made flip-book. The sooty traces of the charcoal and the somewhat crude method come together to convey powerful images of the social explosion that convulsed South Africa in the last decade of the brutal racist regime.

Born in 1955 in Johannesburg, Kentridge came from a family that was part of the small liberal elite in a country where the dominant section of the ruling class had embraced the reactionary doctrine of apartheid. Both sides of his family had emigrated from Russia in the late 19th century to escape the anti-Jewish pogroms, and had risen over several generations from being tradesmen to professionals. Three of his grandparents and both of his parents were lawyers prominent in the anti-apartheid intelligentsia.

Although South Africa was, relatively speaking, an artistic backwater, and was further isolated by boycotts against the regime in the 1980s, Kentridge’s development as an artist was deeply and positively rooted in his first-hand experience of a popular revolution against oppression. His “Soho and Felix” videos about businessman Soho Eckstein and his alter-ego Felix Teitlebaum create memorable images of the exploitation of South African workers in the mines and oil fields.

The work deals not only with the brutality and injustice of the regime, which obviously affected Kentridge, but also with the anguish of the individual. Eckstein may be a cigar-chomping parody of the exploiter—ringing imperiously for his food to be brought to him in bed, answering the clamoring phone and checking the stock tickertape while beneath him in the bowels of the earth, armies of laborers are enslaved—but he is also shown to be isolated, hunted, and trapped.

The work deals not only with the brutality and injustice of the regime, which obviously affected Kentridge, but also with the anguish of the individual. Eckstein may be a cigar-chomping parody of the exploiter—ringing imperiously for his food to be brought to him in bed, answering the clamoring phone and checking the stock tickertape while beneath him in the bowels of the earth, armies of laborers are enslaved—but he is also shown to be isolated, hunted, and trapped.

One of the most haunting images that Kentridge employs in the “Soho and Felix” series is that of water—pouring out of Eckstein’s pockets, dripping down walls, rising up out of nowhere—until it fills everything. Blue is the only color in this predominantly “black and white” world; the various sounds of dripping, gurgling, whispering and rushing water evoke not only tears, but also a longing for redemption of some kind.

“Ubu and the Procession” is the second major theme of Kentridge’s work. In college, he studied theater as well as visual arts. In the mid 1970s, he and fellow students produced Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, the late 19th century satire of the brutality of absolute monarchy and the equal stupidity of the bourgeoisie. Kentridge’s group created its own “theater of the absurd” with the “Fantastical History of a Useless Man,” about “what it felt like to be white and useless in South Africa,” according to Kentridge.

Following the Soweto riots in 1976, Kentridge became involved in the movement against apartheid. Joining with a black theater group to create the theater company Workshop ’71, he acted, directed, and designed sets and posters. For a time, he also designed posters for newly formed trade unions of black workers. A rough-and-ready, agitational quality informs his graphic style even in his later work; he also continues to play a multiplicity of roles in his own productions.

In the 1994 video Ubu and the Procession, a motley collection of downtrodden figures, made of black paper silhouettes, and half-mechanical creatures like a camera tripod, march across the screen in an uprising of sorts, to be driven back by the obese, laughing figure of Ubu (played by Kentridge), with his hooded head and outsized accusatory finger.

A caricature of the vulgar, stupid, and cruel ruling class, the figure of Ubu is transposed to represent the South African state, which established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission in order to stabilize capitalist rule by having the victims of apartheid “forgive” the perpetrators. This was the means by which the African National Congress leadership elevated a thin layer of the black population into the ruling class. The apparent absurdity of the South African bureaucracy in carrying out this political process becomes, in Kentridge’s work, the absurdity of “everyone.” As he has said, “there is a little Ubu in all of us.”

Although Kentridge is generally praised as a political artist, his politics are not clearly spelled out. The central theme is one of disappointment, confusion and resignation in the face of history. As he has himself defined his art, “I am interested in a political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings. An art (and a politics) in which optimism is kept in check and nihilism at bay.”

Like many in his artistic milieu—which in recent years has been associated with theories of post-modernism and identity politics—political issues are viewed in increasingly subjective terms. A virtue is made out of “ambiguity,” but in fact masks a deeper disillusionment. Despite his claims to the contrary, Kentridge’s work, like that of Abramovic over the same period, has become more pessimistic as to the possibility of change in the outside world, and has turned inward.

Hence the theme of the “Artist in his Studio,” the fascination with himself and his own “magical” creative process. While Kentridge is undoubtedly imaginative and prodigious, this part of the exhibit comes across as self-serving.

His more recent work reflects nothing of the social reality in South Africa in the twenty years since the end of apartheid. Where are the scathing satires of the ANC billionaires, the black Ecksteins, counting up their fortunes in their gated mansions, while 70 percent of South Africans still live mired in poverty in what is still one of the most unequal societies on earth?

They are nowhere to be found in Kentridge’s work. Instead he has turned his attention to creating fanciful mechanical theaters that perform Mozart’s “The Magic Flute.”

Kentridge’s perplexity is given further expression in The Horse is Not Mine, his most recent work. Appropriating the traditions of the early Russian avant-garde to create this multi-screen video (which was also projected during his production of The Nose at the Metropolitan Opera), Kentridge claims to have “learned from absurdity” that revolutions are futile.

Splicing together the transcripts of Bukharin’s testimony at the Moscow Frameup Trial of 1937 with documentary images of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, along with his characteristic procession of black silhouettes, his Ubu figure transformed into a giant nose, and a frantically whirling commissar, the meaning behind the frenetic visual imagery—to the extent that a viewer takes the time to work it out—appears to be that all revolutions end in counter-revolutions, replacing one absurd dictatorship with another.

Although their work is not without interest, the bewilderment and pessimism that characterizes most of the recent efforts of both Abramovic and Kentridge is characteristic of a generation, and is bound up with broad social and political trends. These artists were deeply affected by the problems of the past decades, and can only be fully appreciated in that context. Theirs is not the final word, of course. New artists will certainly be heard from in the years to come.