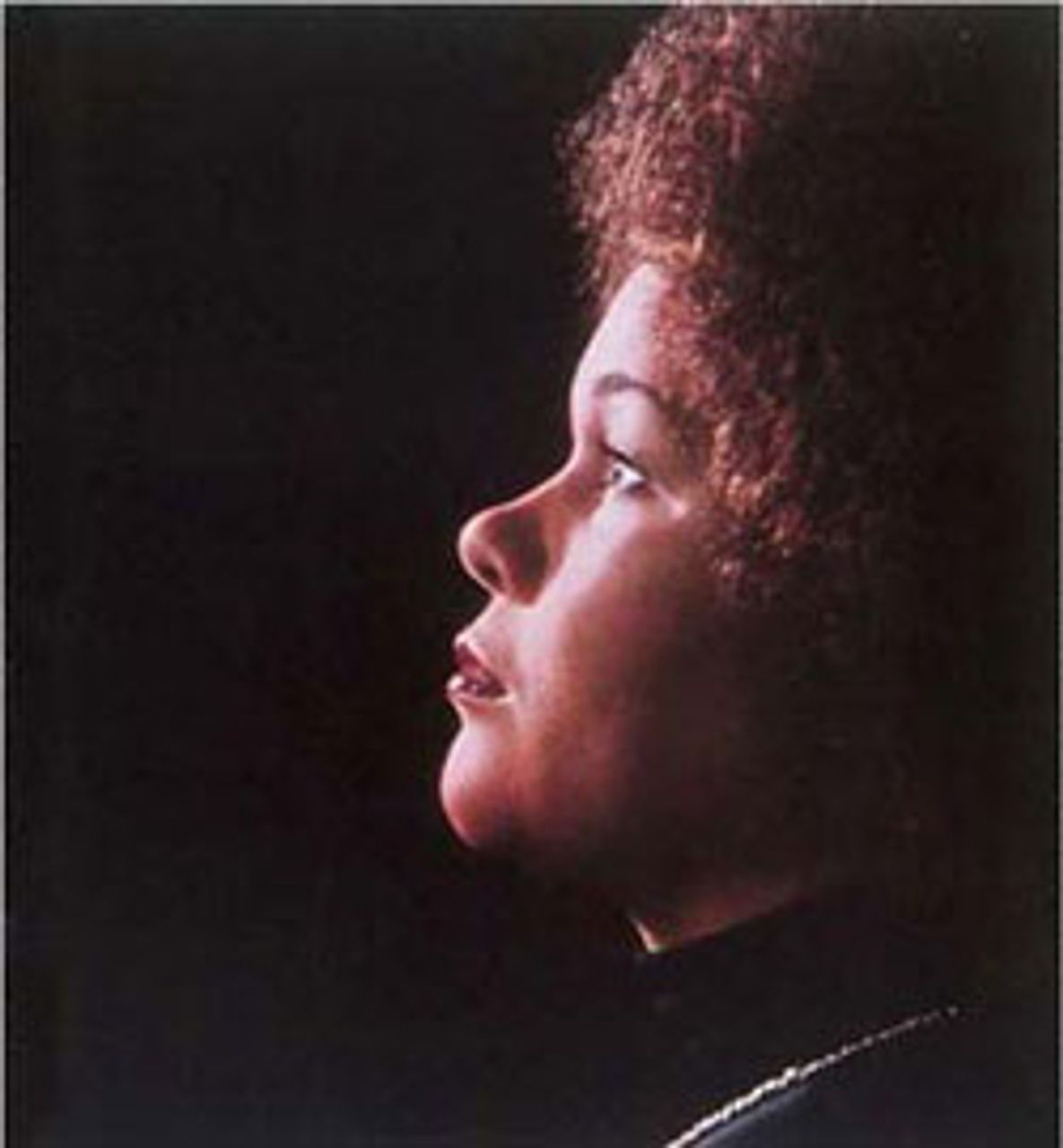

Etta James [Photo: Soul_Portrait]

Etta James [Photo: Soul_Portrait]Etta James died a few days short of her 74th birthday. She had an instantly recognisable voice, sinuous, tender and harsh in equal measure.

The passion and emotional directness in her singing was carried with a rollercoaster stylistic range incorporating jazzy sultriness and a riotous roar that stretched the boundaries of the musical genres within which she worked. She refused to recognise those boundaries, saying that “gospel, country, blues, rhythm and blues, jazz, rock ’n’ roll are all just really one thing. Those are the American music and that is the American culture”.

Such is the lasting influence of her classic recordings that it is surprising to realise how little commercial success she enjoyed at her peak, although widespread recognition did come in her later years. It is also remarkable that her voice remained as consistent and flexible as it did.

Etta James lived a hard life. She was born Jamesetta Hawkins in Los Angeles. Her mother Dorothy was 14. Jamesetta never knew her father, although she always believed he was the white pool player Rudolf “Minnesota Fats” Wanderone. Wanderone would not confirm or deny this, but sent her a photograph that looked, she said, exactly like her eldest son.

Dorothy was frequently absent, and Jamesetta was largely brought up by adoptive parents. She began singing in St. Paul Baptist church in Los Angeles at the age of five. She cited choirmaster Professor James Earl Hines’s role in training her voice. He was her first model as a singer. Hines’s tenor, she wrote later, “was a miracle of flexibility… you never knew what he would throw at you. Vocal variety—that’s what I learned at the tender age of five—vocal fire.”

She later said the key lesson she learned from Hines was “Sing like your life depends on it. Well, turns out mine did.”

She became recognised as an exceptional singer. Her adoptive father hoped to gain from this. Playing poker with his friends he would sometimes wake Jamesetta to sing to them. He insisted she sing all the solos in the choir, until the church told him to take her elsewhere. She was unhappy at this disruption, and attributed her dislike of singing on demand to these experiences. She became determined to sing only what and when she wanted. She later refused to sing in a school glee club.

Jamesetta felt an affinity with the gay members of the choir and defended them. She spent much time later hanging out with drag queens. She had an instinctual hatred of injustice and exploitation.

Dorothy was around, although not regularly or reliably. James wrote that she could not “remember a moment in my mother’s life when she experienced peace of mind.”

When Jamesetta’s adoptive mother died in 1950, Dorothy took her to San Francisco. Their relationship remained fractious—Dorothy did not see James perform live until 1999—but it was influential. She exposed Jamesetta to big band jazz and the music of Billie Holiday. “Mystery Lady”, James’s name for Dorothy, was the title of her 1994 album of songs associated with Holiday.

Dorothy’s absences and trouble with the law allowed Jamesetta leeway. “She was never there when I got off from school, so I could pretty much do what I wanted to do… drinking, smoking weed.” It was the beginning of a lifetime of substance dependencies and difficult relationships.

Although she admired jazz, its technical discipline was less appealing to her adolescent exuberance than the blues. With friends she formed a doo-wop group, the Creolettes, a reference to the lightness of their skins. The Creolettes were already beginning to make a name for themselves around town when they were seen by bandleader Johnny Otis (for obituary see “Johnny Otis, R&B’s renaissance man, dies at 90”).

Otis was impressed and invited them to Los Angeles to record “Roll with Me, Henry,” Jamesetta’s reply to Hank Ballard’s “Work with Me, Annie”. Jamesetta forged Dorothy’s written consent and took to the road.

Otis renamed the group The Peaches, rearranged Jamesetta’s name into Etta James and released the song, retitled “The Wallflower” by Modern Records who thought the original title too explicit. It went to No. 1 on the R&B charts. A follow-up, “Good Rockin’ Daddy”, released after The Peaches had broken up, did well although little success followed.

She toured steadily with Otis and his revue, supporting artists like Little Richard. Her recordings are lifted by the power of her voice. Straightforward rockers are distinguished by her powerhouse approach, while she was also revealing the sultry ache that would characterise her later classics.

In 1959 her Modern contract expired. By now in a relationship with Harvey Fuqua of the Moonglows, she followed him to Chicago’s Chess label. Founders Leonard and Phil Chess were Polish-Jewish immigrants who released records of the burgeoning Chicago blues scene. Leonard engaged her as a writer and singer, seeing her as a balladeer that could break into the pop market and billing her as the “Queen of Soul”.

The results were outstanding. Against Riley Hampton’s rich string arrangements, James’s poignant, bruised voice was at its most seductive on records like “All I Could Do Was Cry” and “At Last”, which became her signature tune. She was not confined to any one style. “Something’s Got A Hold on Me” as seen in this 1962 television performance, was a driving, gospel-inflected number, and her duets with Sugar Pie Desanto recalled the R&B bubblegum of her teens.

The period of her greatest success also saw her turn to heroin. She used it to bolster her confidence, but became addicted.

She was politically radicalised by the struggle for civil rights. She reportedly met with Malcolm X and allied herself with the Nation of Islam under the name Jamesetta X. She continued to call herself a Muslim for around a decade. Her move was driven by social concern, rather than religious sentiment. She said later that “my wildness surely overwhelmed my piety.”

She continued to recognise and identify with the marginalised. Among her criticisms of the 2008 film Cadillac Records (see review “The blues in Chicago: Cadillac Records”) was that Beyoncé Knowles, playing her, was too polished and groomed: “I wasn’t as bourgie as she is. She’s bourgeois. She knows how to be a lady.”

Her addiction led to association with gangsters and criminals, and frequent convictions and jail terms. On one occasion she pawned her band’s instruments to buy heroin. Leonard Chess booked her into a clinic, but she managed only to contract tetanus.

She claimed she received no royalties from Chess and only survived by playing clubs.

Yet she was recording some of her strongest material. In 1967 she released a double-sided single of the driving “Tell Mama” and the aching “I’d Rather Go Blind”. Many of the younger singers who admired her, like Janis Joplin, did not survive the same punishing lifestyle. James always felt a sense of responsibility for Joplin’s early death.

In 1968 she married Artis Mills, a former pimp. More jail time followed. In 1972 both were arrested for possession of heroin. Mills took responsibility and served 10 years. James was committed to a psychiatric hospital.

Her 1974 album “Come A Little Closer” sums up Etta James’s strengths. It shows a continued expansion of her repertoire, featuring the Grammy nominated standard “St Louis Blues” alongside Randy Newman’s “Let’s Burn Down the Cornfield” (about a woman turned on by arson). She included rock songs in her repertoire for the rest of her life.

It was recorded when James was on day-release from the Tarzana Psychiatric Hospital. Because of withdrawal symptoms she was unable to sing “Feeling Uneasy”, and could only moan over the backing track. She never finished the song, and it was released in this form. It is a terrifying and astonishing performance. She said of it later, “Even when I hit emotional bottom my singing didn’t seem to suffer. If anything, I was belting it out like my life was on the line.”

Although she eventually quit heroin, she continued to struggle with addictions. Her records were still well received, but chart success was behind her. She did not record for nearly a decade, but after a spell in the Betty Ford Clinic in 1988 she released the album “Seven Year Itch”. She was joined on it by sons Donto and Sametto, who from then on formed her regular touring rhythm section. James continued to perform despite health problems. She retained all of her ferocity and drive.

Etta James’s singing was truthful. With every song she performed she delivered its powerful emotional content. That feeling was instilled early in her life, and led her to become one of the most expressive voices in the music of the 20th century.