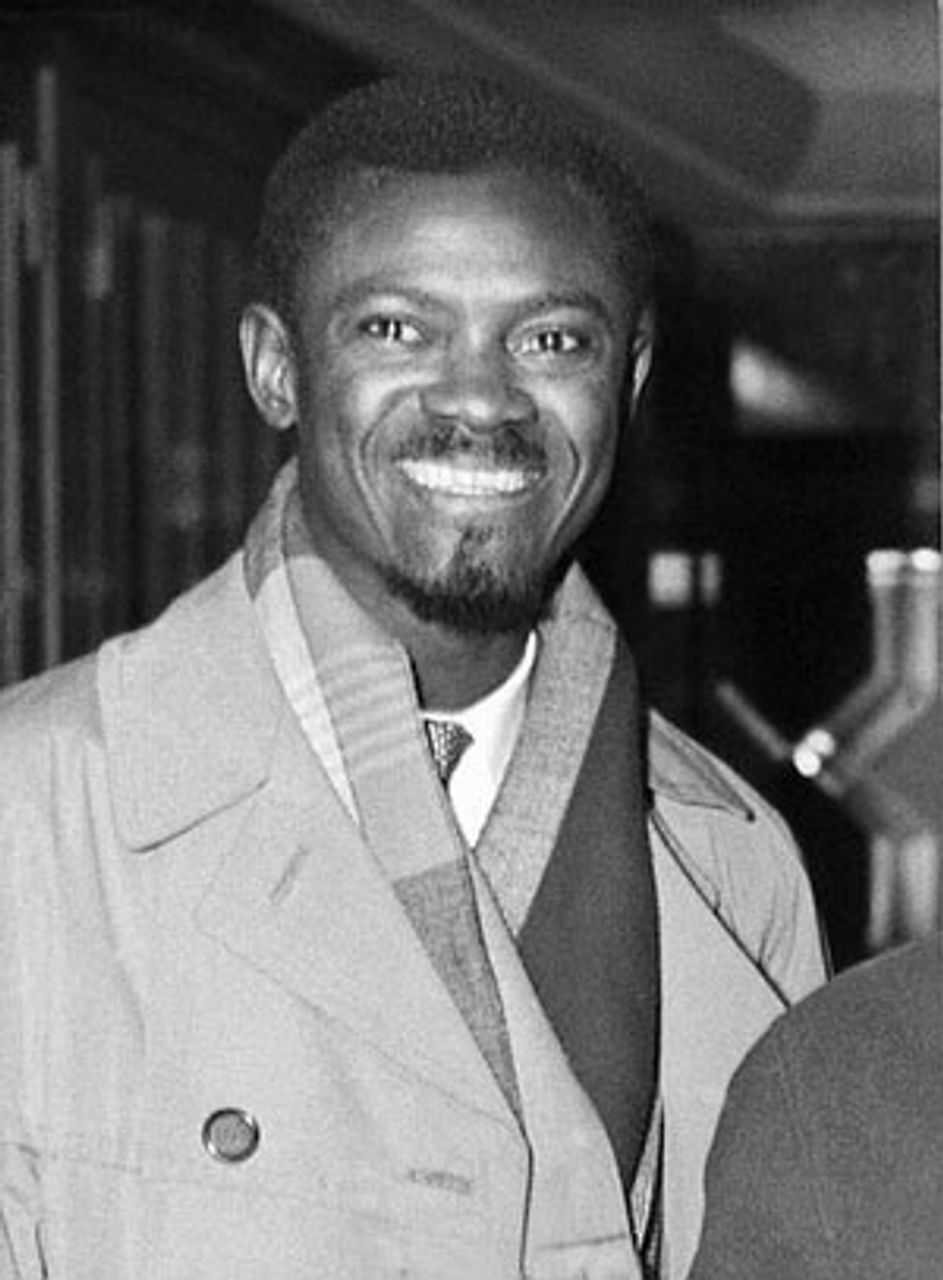

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice LumumbaFifty years ago on January 17, Patrice Lumumba, the leader of the anti-colonial struggle in the Congo and its first democratically-elected prime minister, was removed from prison and murdered in the dark of night by a firing squad acting with the approval of the United States and Belgium. He was 35.

Lumumba and two of his associates, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, were tied to trees and gunned down one by one. Weeks later, when questions surfaced over the official version of Lumumba’s death―that he had been killed by enraged villagers after attempting to escape―the Belgians returned, exhumed the bodies, hacked them up, dissolved them in acid, keeping as souvenirs Lumumba’s teeth and bullets removed from his body.

Belgium, which ruled the Congo until 1960, and the US have never been able to wash away the blood from this grisly crime. There was little doubt at the time, and even less now, that Washington was the primary force behind Lumumba’s execution.

The killing exposed not only the savagery and hypocrisy of US imperialism. It illustrated the hollowness of so-called independence for the African nations, whose absurd boundaries―and indeed very existence as modern political entities―had resulted from the predations of the European powers.

Though not a socialist, Lumumba’s demand that the Congo should control its own extensive mineral wealth proved to be his death sentence. The credibility of all the other newly-independent African nations was lessened by his murder; thereafter in every decision the continent’s leaders would have to reckon with Lumumba’s fate.

Nowhere is the failure of formal national independence better expressed than in the Congo. Lumumba’s former aide, Joseph Mobutu, assumed power in separate CIA-backed coups in 1960, when he removed Lumumba from power, and in 1965. A US proxy in the struggle against liberation movements in southern Africa, Mobutu ruled the Congo, which he renamed Zaire, as a kleptocracy, looting an estimated $5 billion before his removal in 1997 at the hands of invading Rwandan and Ugandan forces. The spilling over into the Congo of the Rwandan crisis of the 1990s―itself the legacy of the European-drawn borders in the region―cost as many as 5 million lives over the next decade.

Joseph Mobutu meeting with Pres. Nixon

Joseph Mobutu meeting with Pres. Nixon in the White House

The Democratic Republic of the Congo’s substantial working class and its tribal populations live in dire poverty. Average life expectancy is but 46 years. Out of every 1,000 live births, 114 Congolese babies will not live to see their first birthday; 195 will not live to the age of five. What little infrastructure exists is in a deplorable state.

Sitting atop this multiethnic and multilingual country of 70 million souls is a tiny layer of multimillionaires who derive their wealth through connections to what is still ranked as one of the world’s most corrupt governments, and through the export of the Congo’s mineral wealth―uranium, copper, gold, tin, cobalt, diamonds, manganese, zinc―for the benefit of European and US corporations.

The rise of Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Lumumba was raised in a mud brick house without electricity in the Congolese region of Kasai. He learned to read and write at Catholic and Protestant mission schools, impressing his teachers and positioning himself for a job as postal clerk in Stanleyville (now Kisangani), which he assumed in 1954. It was here that Lumumba entered political life, working to form a labor union and joining the Belgian Liberal Party.

In 1957, Lumumba took a job as a sales manager at a brewery in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), and soon thereafter founded, with other nationalists, the Movement National Congolais (MNC). The MNC agitated for independence from Belgium and sought to unite the sprawling country’s many different tribal groups.

Lumumba quickly established himself as the leading Congolese nationalist, and in spite of his support for the Belgian Liberals, was considered by the authorities to be a dangerous radical. He was known for his eloquence, and by all accounts was a man of courage and conviction. Perhaps because he could not be bought off, like many African leaders, colonial authorities ordered Lumumba arrested and imprisoned in October of 1959 for “inciting riots” in Stanleyville. While in prison he was tortured.

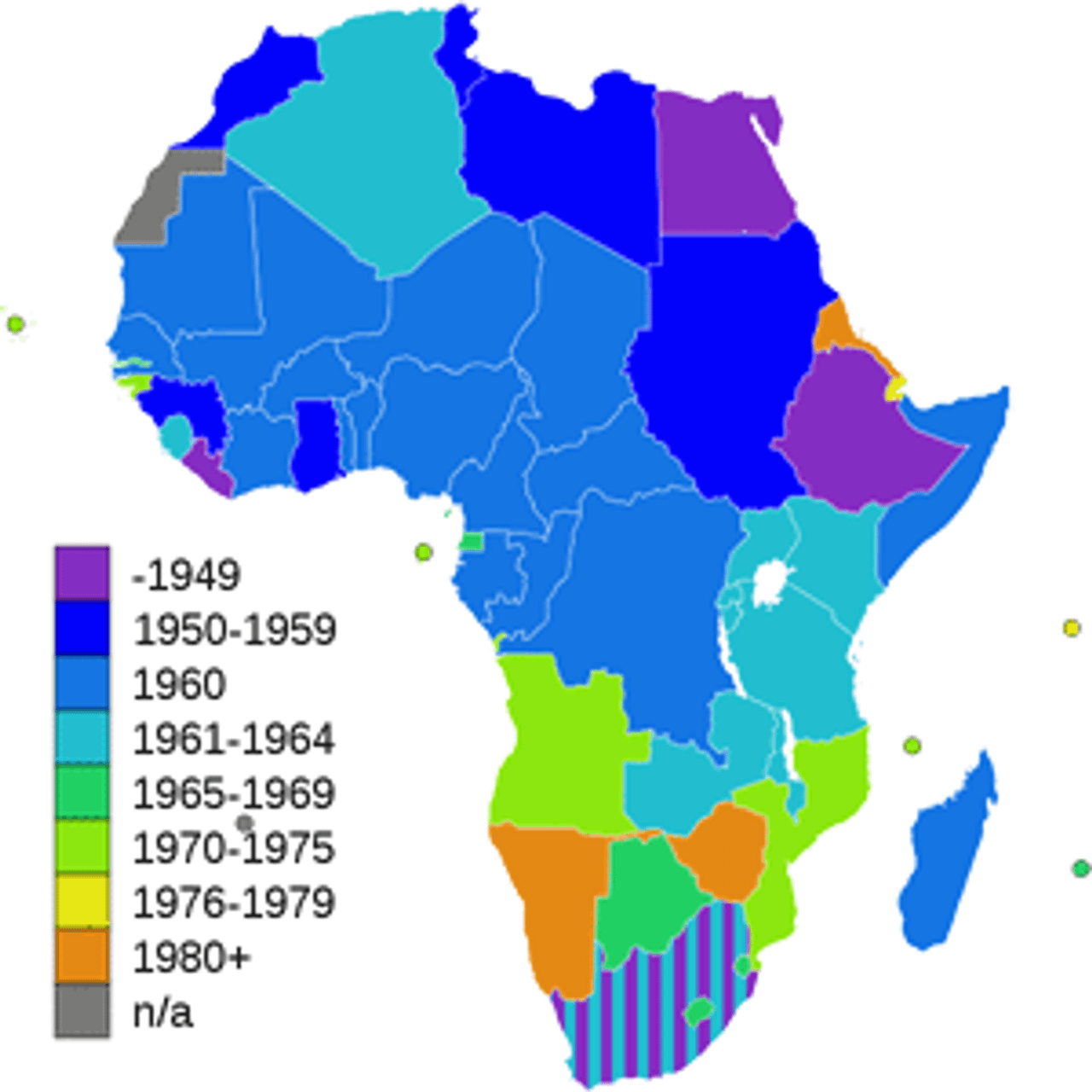

In spite of the repression, it appeared an auspicious time for nationalist movements. In the aftermath of World War II, a revolutionary upsurge of the colonial peoples took shape first in Asia and then spread to Africa. The old colonial powers―Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, and Portugal―either attempted to crush the anti-colonial movements, as France failed to do in Vietnam and Algeria, or else manipulated formal independence to preserve their interests, as Britain did through the communal partition of South Asia.

African decolonization

African decolonizationWith its control over the Congo slipping and mindful of the disaster gripping its neighbor France in Algeria, Belgium agreed at conference held in Brussels beginning January 18, 1960, to recognize the independence of its prized imperial possession. This was to take place at the end of June, after national elections to be held in May. The Belgians were compelled to release Lumumba from prison to attend the conference because his party had gained the most votes in local elections held in December, 1959. In one year less a day, he would be gunned down by Belgian assassins.

Lumumba emerged from the May 11-25 elections, much to the chagrin of the Belgians, as the only truly national figure in Congolese politics. While not winning a majority, the MNC won far more votes and seats in parliament than any other party, and with it the right to form the government. Lumumba was selected as prime minister, while Joseph Kasa-Vubu, the leader of a tribally-based party, was placed in the lesser role of president.

At a ceremony granting formal independence on June 30, King Baudouin of Belgium delivered a patronizing speech lecturing the Congolese on the virtues of maintaining existing colonial structures and presenting the period of Belgian rule as entirely beneficial to the native population. In fact, between 1885 and 1908 as many as eight million Congolese died in the system of forced labor and political terror under the personal rule of Baudouin’s grandfather, King Leopold.

Lumumba being forced to eat his own speech

Lumumba being forced to eat his own speech while under arrest

In his speech, Lumumba enraged the Belgian delegation by openly challenging the king. He said of independence that “no Congolese worthy of the name will ever be able to forget that it was by fighting that it has been won, a day-to-day fight, an ardent and idealistic fight, a fight in which we were spared neither privation nor suffering, and for which we gave our strength and our blood. We are proud of this struggle, of tears, of fire, and of blood, to the depths of our being, for it was a noble and just struggle, and indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force.”

“We have known harassing work, exacted in exchange for salaries which did not permit us to eat enough to drive away hunger, to clothe ourselves, or to house ourselves decently, or to raise our children as creatures dear to us.... We have known ironies, insults, blows that we endured morning, noon and night, because we are negroes.... We have seen our lands seized in the name of allegedly legal laws, which in fact recognized only that might is right.... We will never forget the massacres where so many perished, the cells into which those who refused to submit to a regime of oppression and exploitation were thrown.”

The destruction of Patrice Lumumba

In the same speech, Lumumba declared that the Democratic Republic of the Congo was now “the equal” of Belgium. Only in terms of vote-counting at the United Nations could such a statement be true. All significant capital, especially the mining industry, remained in the hands of Europeans. In all of the Congo, there were only 30 black college graduates, no black military officers, and only a few black managers in the civil service. This was the result of a deliberate Belgian policy to keep the population in a state of dependence.

Mindful of the lack of trained African officers, Lumumba decided immediately after he assumed office to leave the new national army in the charge of Belgians, enraging Congolese soldiers. The Belgian commander of the Leopoldville regiment, Emile Janssens, provoked the African soldiers, gathering them and writing on a placard, “After independence = before independence.” Lumumba made matters worse by granting raises to all government employees except for the military officers.

By July 5, the army was in open revolt across the country, with Europeans fleeing in droves. Belgium seized on the supposed threat to the settlers to recommence military operations in the nation, in open violation of the one week-old country’s sovereignty. To deal with the disaster, Lumumba determined to reorganize the military as the Armee Nationale Congolaise. He made the fateful decision of placing his secretary, Joseph Mobutu, in charge of the new force.

What Lumumba didn’t know was that Mobutu was a paid Belgian agent, and that as early as the 1960 Brussels conference he had been spotted by US diplomats as a figure to be promoted. Of potential “assets” in the Congo, the US ambassador to Belgium, William Burden, noted, "One name kept coming up. But it wasn't on anyone's list because he wasn't an official delegation member, he was Lumumba's secretary. But everyone agreed that this was ... a man with great potential.”

Within days of Lumumba’s inauguration, Moise Tshombe declared Katanga province independent and immediately received the backing of Belgium and its force of 6,000 soldiers stationed there. Katanga was rich in copper, uranium, tin, zinc and cobalt―mineral wealth dominated by the Belgian mining concern Union Miniere. Soon another secessionist movement developed in another mineral-rich province, Kasai, where a former associate of Lumumba, Albert Kalonji, declared a new nation that he dubbed “Mining State.”

The marionettes in the Congo and in Belgium, a third rate and rapidly declining imperialist power, could not act without the backing of the US.

As continues to be the case in matters of foreign policy today, the New York Times played a critical role in articulating the government line and preparing opinion for the elimination of Lumumba.

Even during the election, its pages were given over to a campaign maligning the young nationalist. In a series of articles, the Times repeatedly referred to Lumumba as a “dictator,” a “ruler,” and a “messiah,” and nearly every report mentioned that he was “once convicted of embezzlement” as a postal clerk. The Times also published unsubstantiated allegations that Lumumba had committed election fraud and had received $200,000 from the Belgian Communist Party.

In an August 18 meeting of the National Security Council, US President Dwight Eisenhower told Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) chief Allen Dulles that Lumumba must be “eliminated” so that the Congo would not become “another Cuba.” On August 24, CIA head Allen Dulles cabled station chief Larry Devlin, authorizing the “removal” of Lumumba, up to and including his assassination.

This information did not come to light until 2001. It had been revealed to a US Senate Committee by Robert Johnson, who took notes at the meeting. “There was a stunned silence for about 15 seconds, and the meeting continued,” Johnson recalled in secret testimony given to the Church Committee in 1975. The CIA first followed through on the Eisenhower order with an abortive plot to poison Lumumba.

Assassination plans were also afoot in Belgium. Count Harold d’Aspremont Lynden, then minister for African affairs, sent a telegram to Belgian officials in the Congo in October stating, “The main aim to pursue in the interests of the Congo, Katanga and Belgium is clearly Lumumba’s definitive elimination.”

And Britain, fearful for its substantial interests in neighboring Rhodesia, also endorsed assassination. A British Foreign Office document from September 1960 notes the opinion of a top ranking official, who later became the head of MI5, that, "I see only two possible solutions to the [Lumumba] problem. The first is the simple one of ensuring [his] removal from the scene by killing him."

With the US, Belgium, and Britain moving against him and his hold on power disintegrating, Lumumba turned for support to the USSR, receiving Soviet defense minister Georgi Zhukov in Leopoldville on August 26. The Soviet Union supplied Lumumba with a limited amount of aid and “advisors.” This support only clinched his demise.

On September 5, President Kasa-Vubu ordered that Lumumba be removed from office, but this extra-constitutional order failed when Lumumba won two separate votes of confidence in parliament. Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba then each issued separate orders to Mobutu, as head of the loyal military, to arrest the other.

On September 14, Mobutu, acting with CIA backing, placed Lumumba under house arrest in Leopoldville. Two days later, he carried out a full coup, suspending both parliament and the constitution.

UN General Secretary Dag

UN General Secretary Dag Hammarskjold

The UN under General Secretary Dag Hammarskjöld actively collaborated in bringing down Lumumba. UN “peacekeepers,” who Lumumba had naively invited into the crisis, refused to allow loyal Congolese soldiers use of its airplanes for transport, in effect siding with Katanga and other secessionist movements, and after Lumumba’s vote of confidence the UN shut down the capital’s only radio station so his parliamentary victory could not be broadcast to the population. The UN also blocked Soviet planes supporting Lumumba from using its airfields.

On November 22, 1960, the UN General Assembly voted to recognize the delegation of Kasa-Vubu and military strongman Joseph Mobutu, refusing to sit delegates loyal to the democratically-elected Lumumba.

On November 27, Lumumba escaped from house arrest and attempted to flee to his political stronghold of Stanleyville. He was captured on December 1 by Mobutu’s forces. En route to his prison from Leopoldville airport, Lumumba was put on display in the back of a truck, hands tied and crowds were invited to taunt him. Bound in front of Mobutu, Lumumba was forced to eat a copy of a speech he had given asserting he was the rightful prime minister of the Congo.

Mobutu announced that the deposed nationalist leader would be tried as a rebel. He was then sent off to a military garrison 86 miles from Leopoldville in Thysville. There it is said that Lumumba nearly won the prison guards to his side.

With much of the population still in support of Lumumba, Count d'Aspremont ordered him transferred from Thysville to the renegade Katanga province and certain death at the hands of Tshombe. The move was first cleared with the CIA. During the January 17 flight to Katanga, Lumumba, Mpolo, and Okite were beaten so badly the pilot complained the plane was in danger of crashing. Later in the day the three were executed.

The murder still haunts the US and Belgium. A parliamentary investigation in Belgium in 2001 acknowledged that Baudouin and colonial authorities desired Lumumba’s death and were aware that he would be killed upon his rendition to Katanga, but it stopped short of admitting responsibility.

Frank Carlucci as defense

Frank Carlucci as defense secretary in Reagan administration

Though the US role in the coup and assassination is well-documented, there has never been any official acknowledgment. Frank Carlucci, a prominent Republican with close relations with the Bush political dynasty, who would later rise to defense secretary in the Reagan administration, worked as a covert CIA operative in the Congo under cover of a diplomatic assignment. Carlucci successfully sued to block Lumumba, a film released in 2001, from mentioning his name in the decision to kill the Congolese leader.

Lessons

At the time of independence, the Belgian Congo had, after South Africa, the largest working class in sub-Saharan Africa. The Congolese workers potentially had immense power by virtue of the international importance of the nation’s extractive industries. This was demonstrated through the mass demonstrations and strikes in 1959, when workers in the Congo had played the critical role in forcing the question of independence.

Lumumba was briefly catapulted to power by these developments. But he did not view the working class as the decisive force in the struggle for independence and equality in Africa. Indeed, some of Lumumba’s moves while president―the imposition of tariffs on foreign goods, the breaking of strikes by workers in Leopoldville, and the abortive attempt to maintain Belgian control over the military―may have alienated him, to some degree, from popular sentiment.

The tragedy, however, was the suppression of the central strategic experience of the working class in the 20th century from the African masses: the Russian Revolution and its theoretical elaboration in Trotsky’s theory of the permanent revolution, which had revealed that, as subordinate pieces in the global economy, the capitalists and petty bourgeoisie in the backward and oppressed nations could not achieve even the basic tasks associated with the democratic revolutions of the US and France in the late 18th century. These tasks fell to the working class.

The Stalinist bureaucracy in the Soviet Union and its adjuncts in affiliated Communist Parties all over the world played the critical role in blocking these lessons from the independence struggles. Moscow’s primary aim in assisting Lumumba, as was the case in all of its actions in the global arena, was to gain a bargaining chip to protect its own interests. In accordance with this outlook, it everywhere promoted nationalist politics, including Pan-Africanism, whose hazy plans for political unity on the continent never left the drawing board.

Trotsky’s perspective was vindicated, tragically in the negative, by developments in the Congo and throughout Africa. In every case independence only provided a new color for the domination of imperialism, with corrupt national bourgeois cliques looting the state for their own enrichment. Not even the Pan-Africanists Nyerere, Nkrumah and Kenyatta―whom Lumumba sought to emulate―escaped this fate.

The events taking place over the past several weeks in the North African nation of Tunisia reveal once again the social power and revolutionary potential of the working class. Yet the weakness of the mass movement remains the absence of a clear revolutionary perspective, program and leadership.

Only armed with an international Marxist program can the working masses of Africa be united and the divisions of ethnicity, religion, and nation―stoked by the European powers and the US―be overcome, and the imperialist domination of the continent be broken once and for all.